What is a Photobook?

Until very recently I lived in a perfect world where I only needed two definitions related to photographic works published in books:

- Photography Book, for me, would be any book, with or without text, in which the photograph took the leading role. The book would be just a vehicle for authors to show their work (the photographs).

- Artist Book would be any work of art held in book form. The book as a whole — and not just the photographs within it — would be an art object. Usually handcrafted, they would be unique works or produced in small print runs. Artist books have always been used by artists on different projects in the visual arts and wouldn’t be restricted to photography.

The two concepts take into account photographers as authors of photography works, which excludes other kinds of publications such as catalogs, portfolios and books about photography (stylistic and technical as well as theory books).

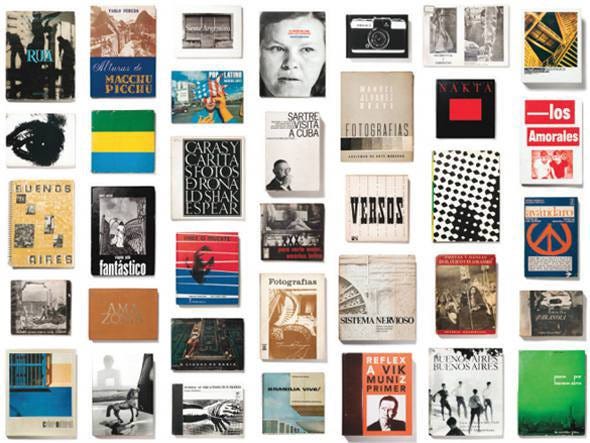

Examples for each term:

With time, however, the term photobook became increasingly popular. At first, I thought it was just another name for a photography book, but the expression has been used to define both what I used to call photography books and artist books.

Then, as my perfect simple world of definitions was crumbling before my eyes, I decided to do some research to find out what exactly a photobook is.

Searching for references related to the word photobook always seems to come to historian and photography critic Gerry Badger. Co-author (with British Photographer Martin Parr) of the three-volume series The Photobook: A History, Badger explains the criteria they used to select the works included in the series, starting from the definition of the term itself:

A photobook is a book — with or without text — where the work’s primary message is carried by photographs. It is a book authored by a photographer or by someone editing or sequencing the work of a photographer, or even a number of photographers. It has a specific character, distinct from the photographic print (…)

This definition matches with that of photography book as I used to understand it, except for that “specific character” he mentions. Badger elaborates about that on an article published by the Brazilian magazine Zum, when defining what would be a photobook:

Photobook is a particular kind of photography book, in which images prevail over text, and the joint work of the photographer, editor and graphic designer helps build a visual narrative.

Elizabeth Shannon, in her The Rise of the Photobook in the Twenty-First Century essay, likes the definition of Ralph Prins better:

A photobook is an autonomous art form, comparable with a piece of sculpture, a play or a film. The photographs lose their own photographic character as things ‘in themselves’ and become parts, translated into printing ink, of a dramatic event called a book.

In the same fashion, Brazilian photographer and visual artist Letícia Lampert published here on Medium an interesting article (in Portuguese) on the similarities and differences between the definitions of photobook and artist book. She points out in that article that photobooks have a narrative that ends in itself, which would set them apart from a catalog or a portfolio.

so, the key point here is the existence of a visual narrative — originated from a specific initial intention — that begins and ends in the book.

The internationally renowned Aperture Foundation, along with the Paris Photo organization, has welcomed the term and since 2012 established a photobook of the year award. The books since then awarded seem to follow the guidelines above. Two examples:

As seen in the examples above, there is a visual narrative (which isn’t always obvious) that would differentiate a photobook from a certain number of photos by an author collected in book form, even if created around a theme like the books on photographs of India by Don McCullin and Steve McCurry.

Attention to form is also a common feature of the photobooks. Different types of paper and page sizes in the same book add layers of interpretation to the visual narrative. Binding alternatives different from the options offered by traditional printers are also frequent.

Book printing and finishing techniques have become much cheaper and more widespread in recent years, allowing photographers more access to these resources, approaching an aesthetic that has always been used in artist books.

Letícia Lampert, quoting Brazilian author Paulo Silveira in the book A Página Violada, says that it is the media that defines the artist book and not its technique, its print run, its concept or its content. The artist book is nothing more than the work of art thought as a book/publication.

In the introduction of The Photobook, a History, Gerry Badger also addresses the role of form when distinguishing the photobook from other photography books by highlighting its intent and an investment in the format, design, aesthetic, and mechanism of ‘the book’.

This attention to the book as an object doesn’t necessarily mean sophisticated papers, cut-outs, and binding techniques. Ed Ruscha’s seminal Twentysix Gasoline Stations, for example, shows this attention precisely through a banal publication, made on cheap paper to be sold for a low price, reflecting, as Leticia Lampert points out, a political stance: ( …) democratize access to art. The features of a photobook are all here: intention, visual narrative and attention to form.

It seems that we already have enough to write down a concept:

Photobook is a kind of photography book, created with a specific intention that is accomplished through editing and graphic design in order to build a visual narrative, with or without an accompanying text, that is an end on itself.

This concept’s main flaw is that it also fits perfectly as an artist book definition. If I wanted to force a distinction between the two, however, I could use the artist book expression to name only the handcrafted books, leaving the concept above to the mechanically produced ones.

So the photobook would be a kind of publication derived from two more traditional ones: the photography book and the artist book.

That’s it. If I add this new concept to the other two I’ve listed at the beginning of this article, my world of definitions related to photographic works in book form would be simple and perfect again.

But no.

There’s an effort by many scholars to classify a particular type of photography book as a photobook intending to institutionalize a specific field of study in Photography. Nevertheless, the term has been used interchangeably for books made by artists, books that only show the photographers’ works (thus devoid of a specific visual narrative) and also the products offered by retailers of personalized photo applications, before known as photo albums (a search on Google for the word “photobook” shows these products on the first results).

So, is it really important that there are so many names for the differet types of photography books?

David Campany says in his article The ‘Photobook’: What’s in a name?:

The term ‘photobook’ is recent. It hardly appears in writings and discussions before the twenty-first century. (…) It seems that makers and audiences of photographic books did not require the term to exist. Indeed they might have benefitted from its absence. Perhaps photographic book making was so rich and varied precisely because it was not conceptualized as a practice with a unified name.

He concludes his essay by saying that he misses those days before the dubious term ‘photobook’ became so widespread. But also that a field needs a name and until we find a better one we’re stuck with ‘photobook’.

Ronaldo Entler sees the “photobook” term as a unifying force around the photography books, He writes in an article (in Portuguese) published by the Brazilian website Icônica:

The movement created around the idea of the photobook was incredibly productive. The importance of editing in photography has been talked about more than ever. Publishers, events, shows and prizes dedicated to photography books were created, and also a web that connects photographers, editors, writers and art directors. At this very moment, authors and small publishers are pushing this market’s boundaries (from printers to distributors) to broaden the access and circulation of the published works. Along with the term “photobook” came a chain of events that already shows its effects.

Some Conclusions

- The term photobook has been used by scholars to define a new field of study in Photography. Their characteristics resemble those of traditional photography books and artist books. The differences between each term are not always easy to spot in order to put this or that book into specific categories, though. The term, however, has become popular in recent years and it’s linked to a growing interest on photography books. It is an expression that, although inaccurate, can’t be ignored.

- The production of books with photographs is quite diverse in form and content and their categorization in little boxes is a hard and unnecessary effort. I believe authors will keep on using the book as a platform for their photographic work regardless of how to sort them or on which shelf to place them.

- For me, the questions that gave rise to this article helped me to clarify the differences between the types of photography books regarding visual narrative. I’ll take these features into consideration for my next projects, but it’s not really important if people will call them photobooks or not.

If you found this post useful, take a second to click on the ❤ and help the story reach more readers like you.

Got a typo? A misused word? Let me know! English is not my primary language and I’d love to learn better (or new) ways to express myself.